Dotoku — the spiritual climate of the land

In the southwestern part of Toyama, where the sankyo-son dispersed settlement lies, there is a word that has been handed down to describe the spiritual climate of the region: dotoku

“Dotoku is probably closer to what Max Weber called ethos. In the Middle Ages, it would have been called ether, the energy of the atmosphere which connects all things” – Hiroshi Ohta, priest of Daifukuji Temple and chairman of the Tonami Folk Art Association

The life of faith and the gratitude in people’s hearts accumulated over dozens of generations have become part of the spiritual climate of the land. It is manifested and felt in many ways, and nurtures people with an invisible force.

The term dotoku is said to have been coined by Soetsu Yanagi, a religious scholar and founder of the Mingei folk art movement, but some believe it has been in the land since ancient times.

What is certain is that the term was commonly used around 1940 to 1955, when Soetsu Yanagi, Shoji Hamada, Kanjiro Kawai, Bernard Leach, and other proponents of the Mingei movement frequented this area.

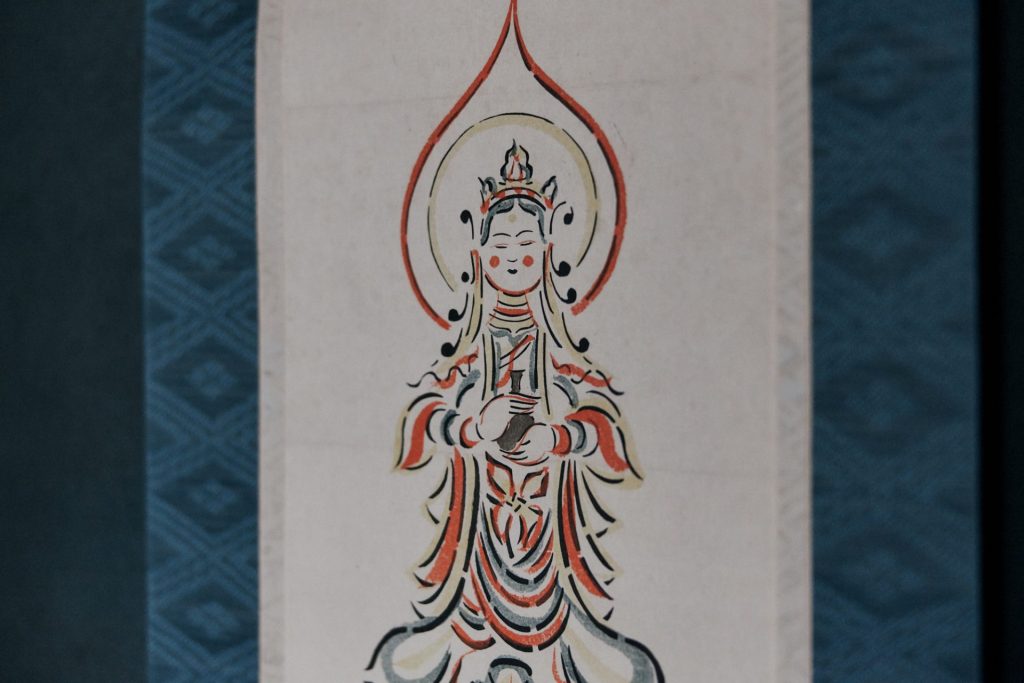

The dotoku which influenced Shiko Munakata and Soetsu Yanagi

From 1945 to 1951, Shiko Munakata evacuated to Fukumitsu in present-day Nanto City. When Yanagi saw the paintings Munakata had done in Fukumitsu, he was surprised by how his work had changed, and felt that the “impurity of egotism” previously present had disappeared, saying “The lines are dynamic, yet contain stillness; the colors are brilliant, yet radiate a mysterious light.”

Living in Fukumitsu, Munakata was undergoing a major inner transformation.

Shiko Munakata himself wrote, “Until now, I had been running around in the world I arrived at with my own power, but in Toyama, the Kingdom of Jodo Shinshu, my feet naturally turned to the world of other-power, and I was enveloped in the vastness of the Buddha’s will…I received a great gift in Toyama. It was the namu amida butsu.” – Shiko Munakata in his autobiography, Bangokudo

Soetsu Yanagi was also struck by an epiphany while staying at Zentokuji Temple in Johana, and wrote The Dharma Gate of Beauty, a definitive work of Mingei aesthetics and a treatise that would become the beginning of his Buddhist aesthetics.

In this mysterious world, everyone, unknowingly, lives as Amida Buddha, surrounded by the vastness of the Buddha’s will.

It was dotoku, the atmosphere of this land that cultivated the potential for epiphany which drew the followers of Mingei here.

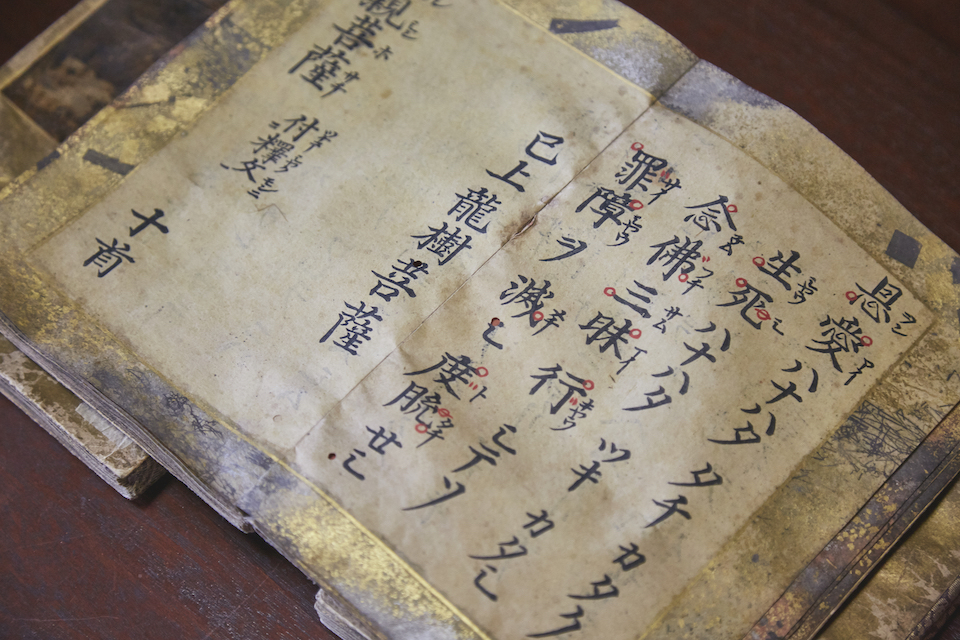

A history of local beliefs passed down from generation to generation

The southwestern part of Toyama Prefecture borders Kanazawa in Ishikawa Prefecture to the west, and Shirakawa in Gifu Prefecture to the south. The plains are an alluvial fan formed by the flow of the Oyabe River and the Shogawa River, and are surrounded on three sides by mountains like a folding screen, except to the north. Gokayama lies at the northern end of the Hida Highlands and has very rugged terrain.

In the Nara period (710-794), Mt. Iozen was opened, and mountain worship and Shugendo (mountain asceticism) flourished, and at one time 48 temples and 3,000 monks’ dwellings were built in the area.

The Jishu sect spread in the Kamakura period (1185-1333), and with the construction of Zuisenji Temple in Inami the Jodo Shinshu faith spread, and the number of Jodo Shinshu temples increased rapidly from the late 1400s to 1600s, when Rennyo Shonin, the 8th head priest of Honganji Temple, came to preach.

The victory of Ikko-shu (Jodo Shinshu) in the Etchu Ikko-ikki revolts also influenced the spread of the faith among the general populace.

It was also during this period that the cultivation of sonkyo-son dispersed settlements expanded to the center of the plains. Although it was a hard life, the more diligently you worked, the richer the harvest, which may have resonated with the Jodo Shinshu teaching to “entrust yourself to the great work.” In a culture imbued with a sense of gratitude for blessings received, the teaching of “other-power” was accepted without any sense of incongruity, became a source of comfort, and spread.

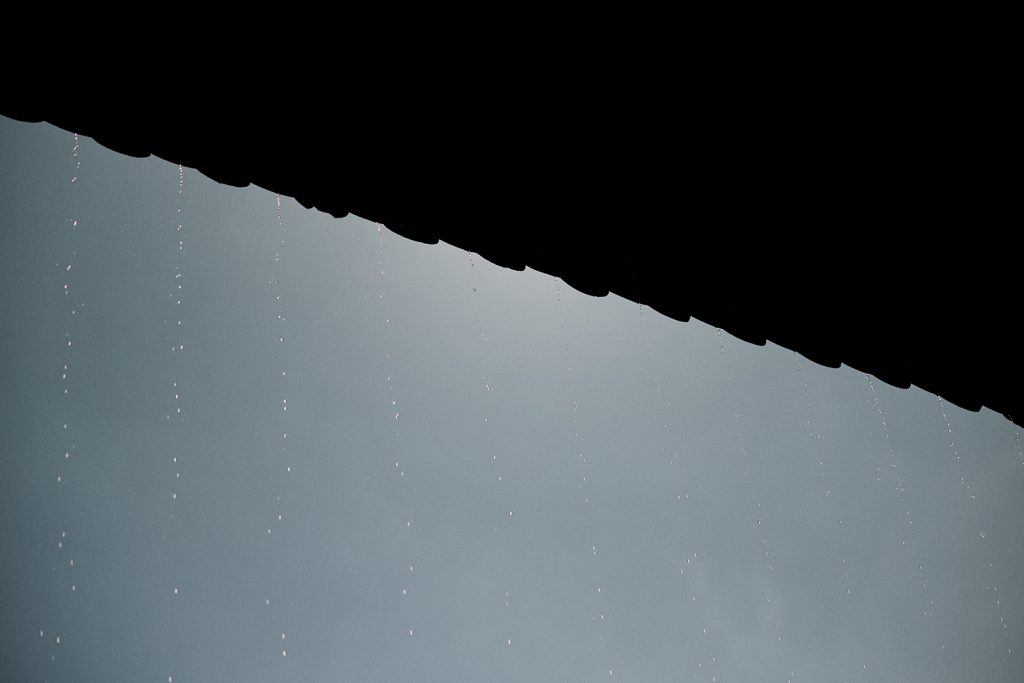

An intuitive grasp of the transcendency and grace of nature lies at the root of faith and religion.

The works of nature can be easily felt in the southwestern part of Toyama prefecture due to the natural environment. Snow which provides water that never runs dry, an alluvial fan surrounded by mountains on three sides, rivers which flow into waterways enabling rice production–these geographical features combined with the distance from the capital have created a region with strong religious feeling which has continued to this day.

This everyday faith is neither pretentious nor doctrinally strict. In the Tonami region, various influences which cannot be divided by religious sect are generously mingled, and over a long time, an atmosphere that can only be described as dotoku has been nurtured and passed on to the present.

Dotoku, in the words of local people

Mizu to Takumi Toyama West Tourism Promotion Association, the management body of Rakudo An, conducted a survey on the relationship between Nanto City and Mingei in 2021 at the request of Nanto City, Toyama. (Nanto Mingei Survey Report)

When we asked the descendents of local priests and people of culture who were once deeply involved with the Mingei movement about dotoku, we received the following responses. Some things stand out when hearing people’s replies to what is ‘dotoku’?

“I think that dotoku is not something special, but something that is born from living in a rooted way. It’s a simple way of living with a clear sense of purpose. Deciding on a destination, a clear goal for life isn’t something we can just create in our minds, but comes through trying to live well as an ordinary person. People say that dotoku exists, but I think instead, it’s something that we have to create.”

“Understanding that ‘things don’t always go as we want them to.’ I think there are opportunities to notice this in the countryside. We tend to think if it’s hot, we can just turn on the air conditioner at our convenience, but in fact our own lives aren’t something which will go just how we like. Adding a religious sense to this, there are times where we have to bow our heads in acceptance. Each part of our daily lives was not something that we arranged by ourselves, but each one was something we received and something we were left in charge of that we inherited without being aware of it. I think the depth of this history was something that resonated with Mr. Yanagi and his colleagues’ sensibilities.”

“I think we can’t do anything without helping each other, and helping each other is a necessary condition for life. However, the word dotoku is not limited to this, I think it’s something which exists all over Japan. I think it’s everywhere, though it feels strange for me to say this.”

“We all have dotoku in our respective lands. We call the joy which is bestowed on us here dotoku, but it is not something we received because of how we are. In order to become a town which is loved by everyone, it’s not about shining our own light, but about everyone shining together, and nurturing dotoku together. It’s about saying “it’s all thanks to you” to those around us. Rather than getting hung up on the meaning of things like “dotoku” and “Mingei”, perhaps the question is how to develop each person’s ability to see, hear, and experience joy.”

Living through entrusting oneself to Buddha, nature, and community was a way of life which was cultivated here, and which narrowly persists to this day. We believe that even a glimpse of this way of life can bring deep learning and awareness to those of us today who live entangled in our egos. In our survey, many were reluctant to claim “we have dotoku here.” Although it is not something that we ourselves created, there is still a sense of unease in claiming to have it. Paradoxically, this reluctance to claim “we have dotoku” seems to be part of dotoku.

Words only point the way, and true understanding is something which is grasped in the body by coming into contact with people, scenery, things, customs, food, and so on which embody dotoku. So the meaning of dotoku is not so much in “understanding” but in coming to feel its importance and becoming interested in it.

Soetsu Yanagi said the following about Buddhist aesthetics:

“It is possible to say that the need for aesthetics is a sign of the degenerate age. It can also be said that it is because the world has become submerged in ugliness that we must have a discourse on beauty. At a time when we are apt to fall into the wrong path, it is necessary to elucidate what true beauty is. In the past, it was not necessary to the same degree because beauty and society were tied together.”

– Soetsu Yanagi, The Promise of Buddhist Aesthetics

Similarly, when dotoku was a natural part of life, its virtues circulated through communities and households and were passed down without needing to put it into words. However, in today’s world when it is in danger of being buried and lost, it may be necessary to give shape to it and pass it on, even if it is difficult to express.

Sources:

Hiroshi Ohta, “Soetsu Yanagi and the dotoku of Nanto”

Nanto Municipal Arts Survey Report “Nanto, a town where the spirit of Mingei lies”

Soetsu Yanagi, “The Dharma Gate of Beauty”

Interview with Kazunari Uratsuji (NPA Zentokuji Cultural Preservation Promotion Association)

History of the towns of Fukumitsu, Johana, and Inami and the villages of Iguchi, Hiramura, Kamihira, and Toga